The Shroud of Turin: A Journey Through Faith and Mystery

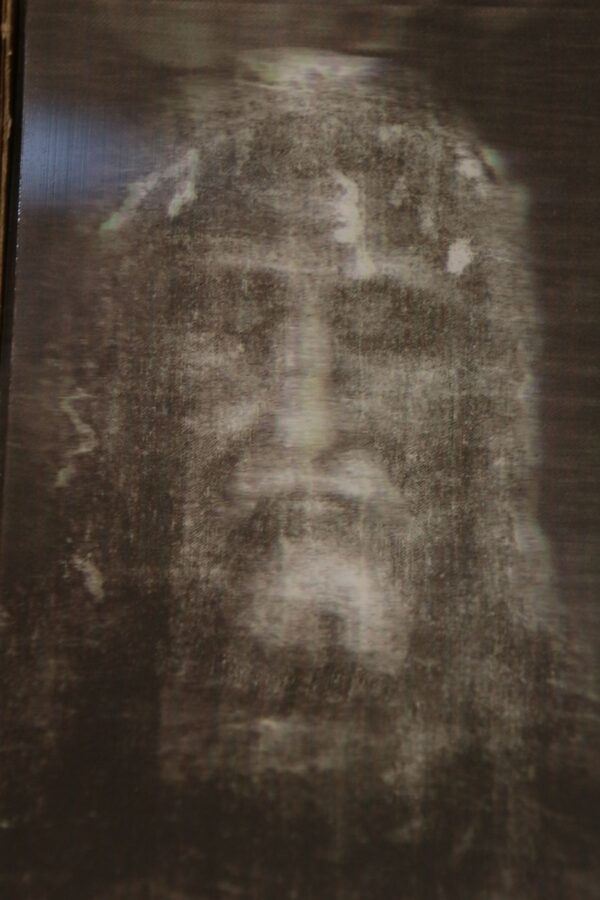

The Shroud of Turin, a precious linen cloth kept in Turin Cathedral, has been the object of devotion and intense scientific and religious debate for centuries. The cloth, approximately 441 cm long and 113 cm wide, depicts a man with signs of torture consistent with crucifixion, and is traditionally identified with Jesus of Nazareth. The term ‘shroud’ is derived from the Greek σινδών, meaning a large cloth, and is now synonymous with this enigmatic shroud.The first certain documentation of the shroud dates from 1353, when the knight Gottfredo de Charny donated it to the church at Lirey, France. However, there are no clear details of how Godfrey came into possession of the shroud. Accusations of forgery appeared in the d’Arcis memorial of 1389, but the veracity of this document is still disputed. In 1390, Antipope Clement VII issued a bull allowing the shroud to be exhibited, but only if it was declared to be a ‘painting’ and not the real shroud of Jesus. Over the following centuries, the shroud passed from one owner to another, including the Dukes of Savoy, and in 1532 it was badly damaged by fire.

The shroud was later repaired by the Poor Clare nuns of Chambéry and was displayed again in 1534. In 1578, the shroud was transferred to Turin, where it remains today. The chapel designed by Guarino Guarini, where the Shroud was placed in 1694, became its permanent home, except for a brief move to Genoa during the French siege of 1706 and a hiding place in Montevergine, Campania, during the Second World War. In 1946, the shroud was returned to Turin. Scientific interest in the Shroud increased significantly in 1898, when the lawyer Secondo Pia discovered that the image on the Shroud appeared as a photographic negative, revealing details that were invisible to the naked eye. Subsequent studies, including photographs by Giuseppe Enrie, confirmed this discovery. In 1959 the International Centre of Sindonology was founded and in 1973 direct scientific studies began. In 1988, however, a carbon-14 test dated the shroud between 1260 and 1390, a period corresponding to the earliest certain documentation.

This result, disputed by some scholars because of possible contamination, did not end the controversy. Other studies, such as one in 2002, attempted to preserve the shroud by removing the patches and replacing the damaged backing. The sheet shows burn marks and visible damage, but its dimensions and texture have been carefully analysed. Controversies over the Shroud’s authenticity also include the question of alleged coin images on the eyes and blood drips. Some scholars argue that the blood may have been removed before the body was wrapped, while others dispute the presence of coins due to the low resolution of the photographs.

Today, the shroud continues to attract millions of pilgrims and stimulate scientific and religious debate. The Catholic Church, while taking no official position on the authenticity of the Shroud, permits its veneration as a relic. Protestant churches, on the other hand, consider the veneration of the shroud as a manifestation of popular religiosity. New studies, such as those carried out with X-rays in 2024, suggest a date of around two thousand years ago, but the reliability of these results remains a matter of debate. The Shroud of Turin therefore remains a fascinating mystery, a meeting point between faith and science that continues to raise questions and surprises.